To Assess the Outcome of Balloon Aortic Valvuloplasty in Children with Special Reference to Dooming Versus Dysplastic Valve

Nishat Fatima*

Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Children Hospital and ICH, Lahore, Pakistan

- *Corresponding Author:

- Nishat Fatima

Department of Pediatric Cardiology,

Children Hospital and ICH,

Lahore,

Pakistan,

Tel: +92 3049011900;

E-mail: nishatasghar23@gmail.com

Received date: April 16, 2023, Manuscript No. IPPECM-23-16402; Editor assigned date: April 19, 2023, PreQC No. IPPECM-23-16402 (PQ); Reviewed date: May 03, 2023, QC No. IPPECM-23-16402; Revised date: June 16, 2023, Manuscript No. IPPECM-23-16402 (R); Published date: June 23, 2023, DOI: 10.36648/IPPECM.8.01.001

Citation: Fatima N, Hyder SN, Ghous M (2023) To Assess the Outcome of Balloon Aortic Valvuloplasty in Children with Special Reference to Dooming Versus Dysplastic Valve. Pediatr Emerg Care Med: Open Access Vol:8 No:1.

Abstract

Background: Because of limited available congenital cardiac surgery facilities in country like us, balloon aortic valvuloplasty is the preferred choice of intermediate treatment irrespective of age and valve morphology.

Objective: The objective of this research was to observe the success rate of balloon aortic valvuloplasty in children with special reference to dooming versus dysplastic valve.

Method: A retrospective study with simple random sampling was performed by developing performa and the reliability of performa was verified by using the Cronbach’s Alpha. Performa of all children admitted to angiography department of cardiology, university of child health, Lahore for aortic balloon valvuloplasty was filled from December 2021 for 6 months after ethical committee approval. The data was entered in SPSS version 25 and analyzed for statistically significant outcomes. Descriptive analysis was used, the Chi square test and paired t-test was applied.

Results: A total 54 children upto 15 years with male to female ratio of 2:1 were treated with aortic balloon valvuloplasty. 45 patients were non-dysplastic aortic valve, and 9 patients were dysplastic valve. The pre procedural pullback pressure gradient decreased of 60.37 (SD ± 29.6) mmHg to 24.96 (SD ± 15.4) mmHg. 24 children developed post procedural aortic regurgitation. 11 (45%) are children of less than 1 year of age and 13 (54%) are children of age between 1 to 15 years of age.

Conclusion: It was concluded that aortic balloon valvuloplasty is better option of intermediate treatment in children where there is limited congenital cardiac surgery facilities.

Keywords

Aortic stenosis; Aortic balloon valvuloplasty; Pullback pressure gradient; Dysplastic aortic valve; Aortic regurgitation

Abbreviations:

AV: Aortic Valve; BAV: Balloon Aortic Valvuloplasty; LV: Left Ventricles; LVOT: Left Ventricular Out Flow Track; MPG: Mean Pressure Gradient; PPG: Pullback Pressure Gradient; AR: Aortic Regurgitation

Introduction

Isolated valvular aortic stenosis comprises 5% of congenital heart disease with male dominance [1]. It is a long lasting condition often required multiple procedures. Balloon Aortic Valvuloplasty (BAV) in children was first reported in 1983 by Lababidi [2]. Currently it becomes the preferred early intermediate treatment in children. The treatment options depend on local expertise and institutional preference and associated complication like development of cardiac failure, aortic regurgitation and repeated intervention and death [3]. BAV become safe and effective due to improvement in technique and introduction of low profile balloons [4,5]. There are many surgery options in aortic stenosis i.e from simple commissurotomy to valve reconstruction [6].

Morphologically, 63% aortic stenosis presented with bicuspid valve, 14% with unicuspid valve and 11% with dysplastic valve [1,2]. Unicuspid morphological valve usually presented at neonatal age [3].

It remained controversial regarding initial treatment option i.e. surgery versus transcather in young children. The CHD surgeons society demonstrated same result between surgery and balloon valvuloplasty in neonates and infants [7]. In country like us where due to limited resources and available congenital cardiac surgery facilities BAV now considering save early treatment option. Few local studies available regarding the outcome with regard to dysplastic versus non-dysplastic valve. Therefore, this study was selected to share the experience.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective study with simple random sampling performed to assess success rate of balloon aortic valvuloplasty from neonate to 15 years of age by a semi structured, close ended questionnaire as a data collecting tool after pretesting to check the reliability of the questionnaire. Data collected from angiography department of university of child health science Lahore, after the approval of institutional review board. Duration of study was 6 months from December 2021 to onward.

The questionnaire had mainly three parts. The first part contained information regarding demographic data like age and gender. The second part consisted of aortic annulus, aortic morphology, preprocedure and post procedural aortic and LV pressures. The third part was about the complications of this procedure.

Inclusion criteria

• All children having isolated aortic stenosis.

• Age group from neonate to 15 years of life.

Exclusion criteria

• Small LV with no apex formation or small mitral valve by Zscoring.

• Shone complex physiology.

• Multiple valvular diseases.

• Primary pulmonary hypertension.

• Those children in which previous cardiac surgery done.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography was done on a VIVID-95 GE machine. The echocardiographic parameters taken were:

• Morphology of aortic valve (unicuspid, bicuspid, tricuspid),

• Annulus size measured at parasternal long axis and short axis view.

• Maximum peak gradient at the suprasternal view or right upper parasternal view.

• Aortic valve regurgitation grade.

Considered mild if color jet did not go beyond anterior mitral valve leaflet and width was less than 30% of the LVOT. Similarly, moderate AR considered when jet goes distal to AML and jet width covered more than 30% of LVOT. Severe AR was defined if jet length goes more than mid LV cavity and width covered more than 50% of LVOT and retrograde flow in descending aorta of more than 40 cm/sec and moderate to severely dilated left ventricle [8,9].

• Thin pliant valve that domed during systole term dooming valve.

• Thick non-pliant valve that moved like a board term dysplastic valve [9].

Angiocardiography

The balloon aortic valvuloplasty was done under general anesthesia with all septic technique. Mostly arterial assess taken from femoral side. Heparin with 75 IU/kg-100 IU/kg was used prior to the procedure.

Aortogram done at Left Anterior Oblique (45 LAO) and pressure was recorded and valve annulus was measured. The balloon size was selected upto 0.8%-0.9% of annulus size according to weight.

The right ventricle over drive temporary pacing used during balloon inflation time to stabilize the balloon. Post procedure peak pressure measured and post ballooning angiography done to see the result.

The result was considered adequate if gradient difference was below 35 mmHg with no or trivial AR or upto 50% fall in peak systolic gradient. Similarly, the result was considered inadequate if gradient was above 35 mmHg with moderate to severe AR [10].

Statistical analysis

All the data was entered in SPSS version 22 and then analyzed for statistically significant outcomes. Descriptive analysis used to describe the basic features of the data, the Chi square test and paired t test is used.

Results

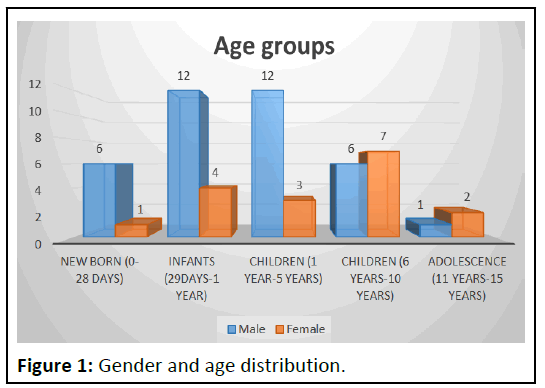

A total of 54 children 37 (68%) were males and 17 (32%) were females with ratio of 2:1. The age included 6 (11 %) newborn, 17 (31%) infants, 28 (52%) were children of age 1 to 10 years and 3 (5.6%) were up to 15 years (Figure 1). According to valve morphology 1.9% had unicuspid, 40.7% had bicuspid and 57.45% had tricuspid aortic valve stenosis. 9 (16.7%) patients had dysplastic aortic valve and 45 (83.3%) were non-dysplastic. From the total of 9 dysplastic aortic valve, 8 (89%) were bicuspid aortic valve and only 1 (11%) was tricuspid (Table 1).

| Morphology | Unicuspid valve | Bicuspid valve | Tricuspid valve | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-dysplastic | 1 (1.9%) | 14 (25.9%) | 30 (55.5%) | 45 (83.3%) |

| Dysplastic | 8 (14.8%) | 1 (1.8%) | 9 (16.6%) | |

| Total | 1 (1.9%) | 22 (40.7%) | 31 (57.4%) | 54 (100%) |

Table 1: Frequency distribution of aortic valve morphology.

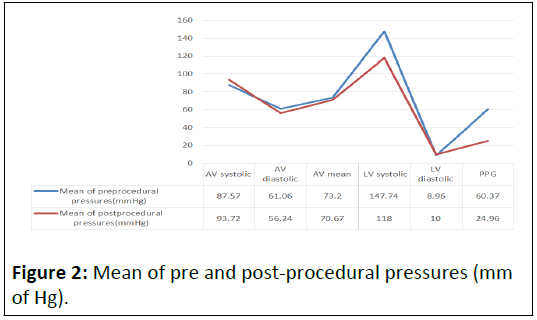

The mean preprocedural aortic systolic pressure was 87.57 (SD ± 19.3) mmHg and diastolic pressure was 61.06 (SD ± 13.8). The mean post procedural aortic systolic pressure was 93.72 (SD ± 18.1) mmHg and post procedural aortic diastolic pressure was 56.24 (SD ± 15) mmHg. The Pullback Pressure Gradient (PPG) decreased from 60.37 (SD ± 29.6) mmHg to 24.96 (SD ± 15.4) mmHg after balloon aortic valvuloplasty (Figure 2).

The mean pullback pressure gradient of non-dysplastic aortic valve decreased from 63.36 ± 29.9 to 26.4 ± 14.3 after the procedure. It decreased to almost 36.96 (63.36–26.4). The mean pullback pressure gradient of dysplastic aortic valve was decreased form 45.5 ± 24.7 to 17.78 ± 19 after the procedure. It decreased to 27.72 (45.5–17.78) that indicated partial result (Table 2).

| Dysplastic AV | Pre procedural PPG | Post procedural PPG |

|---|---|---|

| No | 63.36 ± 29.9 | 26.40 ± 14.3 |

| Yes | 45.5 ± 24.7 | 17.78 ± 19 |

Table 2: Pre procedural and post procedural PPG of dysplastic versus non-dysplastic AV.

The complications developed during procedure noted that rhythm problems in 3 children and 1 baby went to cardiac arrest who was resuscitated and revived. 1 death during procedure was happened because that neonate was referred at critical sick condition with severe LV dysfunction and could not revived. Similarly, mild and moderate AR more commonly developed in dysplastic valve (Table 3). Age break down of complication revealed that 11% were newborn (0-29 days), 7.4% were infants (1 m to 1 year) and 7.4% were children (6 years to 10 years) and no complication developed above 10 years. The association (p=value) of complication with age, gender, valve morphology with dysplastic valve showed no significance (p=≥ 0.04) but per and post procedural AR were associated with complication (p=≤ 0.04) (Table 4).

| Groups | Types | Non-dysplastic | Dysplastic | Number (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhythm problems | Bradycardia | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Ventricular fibrillation | 1 | 1 | ||

| Cardiac arrest | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Aortic regurgitation | Mild | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Moderate | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Severe | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Others | Bleeding | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Pericardial effusion | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Blockage of femoral artery | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Death | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Table 3: Complications developed during aortic balloon valvuloplasty.

| Variables | Chi-square value | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 32.276 | 0.12 |

| Gender | 4.336 | 0.631 |

| AV morphology | 7.263 | 0.84 |

| Dysplastic AV | 7.506 | 0.277 |

| Pre procedural AR | 16.315 | 0.012 |

| Post procedural AR | 23.381 | 0.025 |

Table 4: Association of complications with age, gender, morphology and AR.

The difference between pre and post procedural pull back gradient is significant value (p 0.04; paired t-test). The mean difference between pre procedural and post procedural pull back gradient was 35.4 mmHg (SD ± 25.7 mmHg) with the standard error mean of 3.5. Pull back gradient after balloon aortic valvuloplasty was less than before the procedure. This means that difference in left ventricular an d aortic pressure decrease (Table 5).

| Paired differences | t | Sig. (2-tailed) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard deviation | Standard error mean | 96% Confidence interval of the difference | |||||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Pair 1 | Pre procedural aortic systolic pressure-post procedural aortic systolic pressure | -6.148 | 20.284 | 2.76 | -11.685 | -0.612 | -2.227 | 0.03 |

| Pair 2 | Pre procedural aortic diastolic pressure-post procedural aortic diastolic pressure | 4.815 | 12.648 | 1.721 | 1.363 | 8.267 | 2.797 | 0.007 |

| Pair 3 | Pre procedural aortic mean systolic pressure-post procedural aortic mean systolic pressure | 2.537 | 18.505 | 2.518 | -2.514 | 7.588 | 1.007 | 0.318 |

| Pair 4 | Pre procedural LV systolic pressure-post procedural LV systolic pressure | 29.741 | 24.836 | 3.38 | 22.962 | 36.52 | 8.8 | 0 |

| Pair 5 | Pre procedural LV diastolic pressure-post procedural LV diastolic pressure | -1.037 | 6.988 | 0.951 | -2.944 | 0.87 | -1.091 | 0.28 |

| Pair 6 | Pre procedural pullback pressure gradient-post procedural pullback pressure gradient | 35.407 | 25.717 | 3.5 | 28.388 | 42.427 | 10.117 | 0 |

Table 5: Paired t test of pre procedural and post procedural pressures (mmHg).

Discussion

Due to complex morphology of congenital aortic stenosis treatment is always controversial. The ultimate treatment considers to be Ross or valve replacement [11]. In low socioeconomic country because of limited surgical facilities BAV is preferred initial option [9]. After development of more centers and expertise in our country BAV consider to be safe and effective intermediate treatment option especially in LV dysfunction [12,13]. Our study revealed mild complication rate of 23% which supported other study. Regarding valve morphology 57.4% were tricuspid valve, 40.7% had bicuspid and 1.9% had unicuspid valve as supported by other study. We also observed development of AR and other complication in dysplastic valve [14].

Therefore, in low socioeconomic country like Pakistan where due to limited resources and poor referral and lake of congenital cardiac surgery support BAV is save and better option for intermediate relive to the critical children having congenital aortic stenosis. Our experience showed satisfactory outcome both in dysplastic and dooming valve morphology.

Conclusion

It was concluded that aortic balloon valvuloplasty is better option of intermediate treatment in children where there is limited congenital cardiac surgery facilities.

Limitations of study

We only selected isolated congenital valvular stenosis and excluded more complex aortic stenosis like shown complex. Small sample size, single centered study, conducted in limited area with limited patients reflected limited statistical and predictor value. Similarly, long term follow up along with surgical groups were missing.

Acknowledgement

We would like to appreciate the angiography staff and record keeper and echo technician of university of child health sciences, Lahore.

Conflict of Interest

There was no conflict of interest in this study.

Funding

Nil.

References

- Hoffman JI, Christianson R (1978) Congenital heart disease in a cohort of 19,502 births with long term follow-up. Am J Cardiol 42:641–647

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lababidi Z (1983) Aortic balloon valvuloplasty. Am Heart J 106:751-752

- Hochstrasser L, Ruchat P, Sekarski N, Hurni M, Von Segesser LK (2015) Long term outcome of congenital aortic valve stenosis: Predictors of reintervention. Cardiol Young 25:893-902

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Auld B, Carrigan L, Ward C, Justo R, Alphonso N, et al. (2019) Balloon aortic valvuloplasty for congenital aortic stenosis: A 14 years single centre review. Heart Lung Circ 28:632–636

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saung MT, McCracken C, Sachdeva R, Petit CJ (2019) Outcomes following balloon aortic valvuloplasty versus surgical valvotomy in congenital aortic valve stenosis: A meta analysis. J Invasive Cardiol 31:E133–E142

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui J, Brizard CP, Galati JC, Iyengar AJ, Hutchinson D, et al. (2013) Surgical valvotomy and repair for neonatal and infant congenital aortic stenosis achieves better results than interventional catheterization. J Am Coll Cardiol 62:2134–2140

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McCrindle BW, Blackstone EH, Williams WG, Sittiwangkul R, Spray TL, et al. (2001) Are outcomes of surgical versus trans catheter balloon valvotomy equivalent in neonatal critical aortic stenosis? Circulation 104:I152–I158

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lima VC, Zahn E, Houde C, Smallhorn J, Freedom RM, et al. (2000) Non-invasive determination of the systolic peak to peak gradient in children with aortic stenosis: Validation of a mathematical model. Cardiol Young 10:115-119

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wazir HD, Qureshi AU, Hyder SN, Sadiq M (2019) Immediate and midterm results of balloon aortic valvuloplasty in children with aortic valve stenosis with special reference to dysplastic aortic valve. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 31:517-521

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Porras D, Brown DW, Rathod R, Friedman K, Gauvreau K, et al. (2014) Acute outcomes after introduction of a Standardized Clinical Assessment and Management Plan (SCAMP) for balloon aortic valvuloplastyin congenital aortic stenosis. Congenit Heart Dis 9:316–325

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mc Crindle BW, Blackstone EH, Williams WG, Sittiwangkul R, Spray TL, et al. (2001) Are outcomes of surgical versus transcatheter balloon valvotomy equivalent in neonatal critical aortic stenosis? Circulation 104: I152–1158

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Torres A, Vincent JA, Everett A, Lim S, Forester SR, et al. (2015) Balloon valvuloplasty for congenital aortic stenosis: Multi center safety and efficacy outcome assessment. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 86:808-820

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soulatges C, Momeni M, Zarrouk N, Moniotte S, Carbonez K, et al. (2015) Long term results of balloon valvuloplasty as primary treatment for congenital aortic valve stenosis: A 20 years review. Pediatr Cardiol 36:1145-1152

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holzer RJ, Cheatham JP (2010) Shifting the balance between aortic insufficiency and residual gradients after balloon aortic valvuloplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol 56:1750-1751

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences